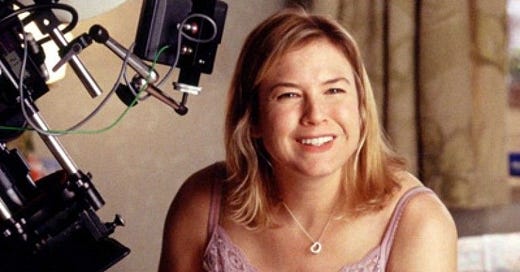

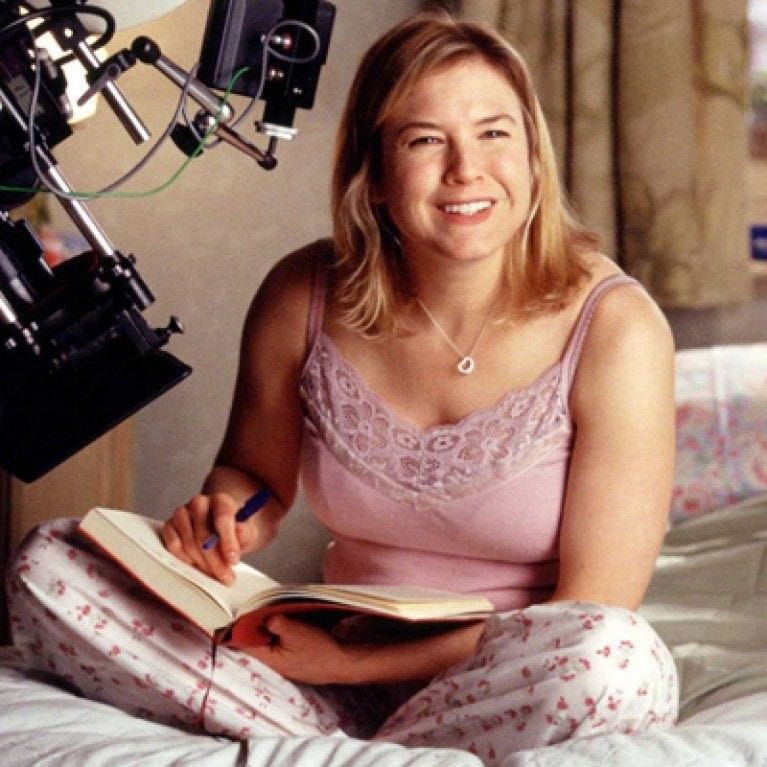

if i told you i have never scoffed at the phrase “chick lit” or “chick flick,” i would be lying, but i don’t necessarily think it’s my fault that i felt that way. i don’t know when it happened, but somewhere along the way, growing up in our formative years, we were taught that stories centering women—especially when they involved love, friendship, or any kind of emotional excess—were frivolous.

in tandem with this, things that were deemed girly came with a condescending undertone: girly meant unserious. add in the colour pink—which has long been associated with femininity—was treated as a visual shorthand for weak, silly, or overly emotional. (and yes, we should also talk about how assigning gender to a colour is weird, but that’s a different post.)

so i grew up thinking everything related to girlhood-to-womahood was unserious, as it was portrayed in pop culture, and that the issues boys and men faced should be taken more seriously.

things that girls and women enjoyed were guilty pleasures, while the things that boys and men liked held merit.

which brings me back to the chick lit and chick flick drawing board. even though it’s a relic from the 1990s and the early 2000s, the way it was dismissed then as ‘lesser than’ still echoes how we talk about women’s fiction now.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to cool gal writing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.